If you have fond memories of the batting cages on Stillwell Avenue, the International Speedway Go-Karts, the Jumbo Jet Roller Coaster, the Dragon's Cave on the Bowery, or the 1970s revived Steeplechase Park located on the site of the original, then you've had a taste of Norman Kaufman's Coney Island vision. He was known for his amusements, but his epic battle with Fred Trump was legendary.

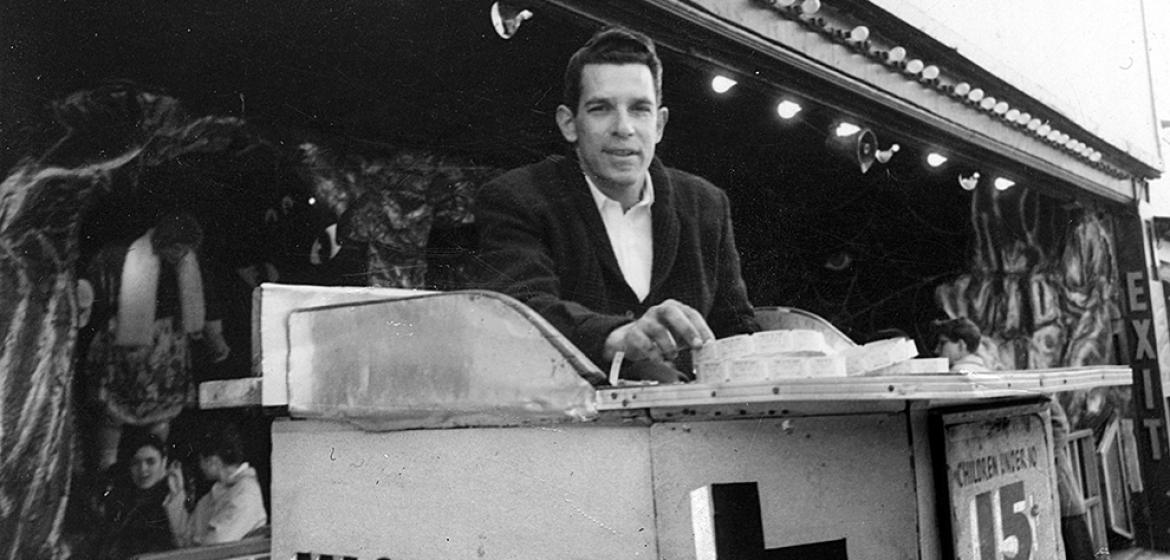

Norman Kaufman, who passed away last November, was born in Coney Island and remained a force there for eighty years. His family operated the famous Mayflower photo studio and souvenir stand on Surf Avenue during the 1930s. "I began working in a darkroom at the age of eleven," Norman said, "developing photos for twenty cents an hour before automatic picture machines were invented." The photo studio's main prop was an old wooden rowboat named the "Mayflower" that enabled generations of immigrants to have their picture taken arriving in America as "Pilgrims."

During the 1940s, the Kaufman family operated the infamous World War II "atrocity show" in the Lido Hotel on Surf Avenue in partnership with Messmore and Damon, who manufactured the show's animated figures. When the attraction closed in the 1960s, Norman reclaimed many of the show's figures and used them in the family's bizarre spook house, the Dragon's Cave.

Norman and his brother, Sporty, had transformed their "Fun in the Dark" dark ride into a Bowery landmark whose entrance was topped with an animated smoke-belching dragon that swiveled above the crowds waiting in line. Norman had a hand in many Coney Island businesses. He managed the Log Flume ride in Astroland Park and later opened a slot-car raceway in a Surf Avenue storefront.

The fire-breathing Dragon at the Dragon's Cave. © Charles Denson, 1971

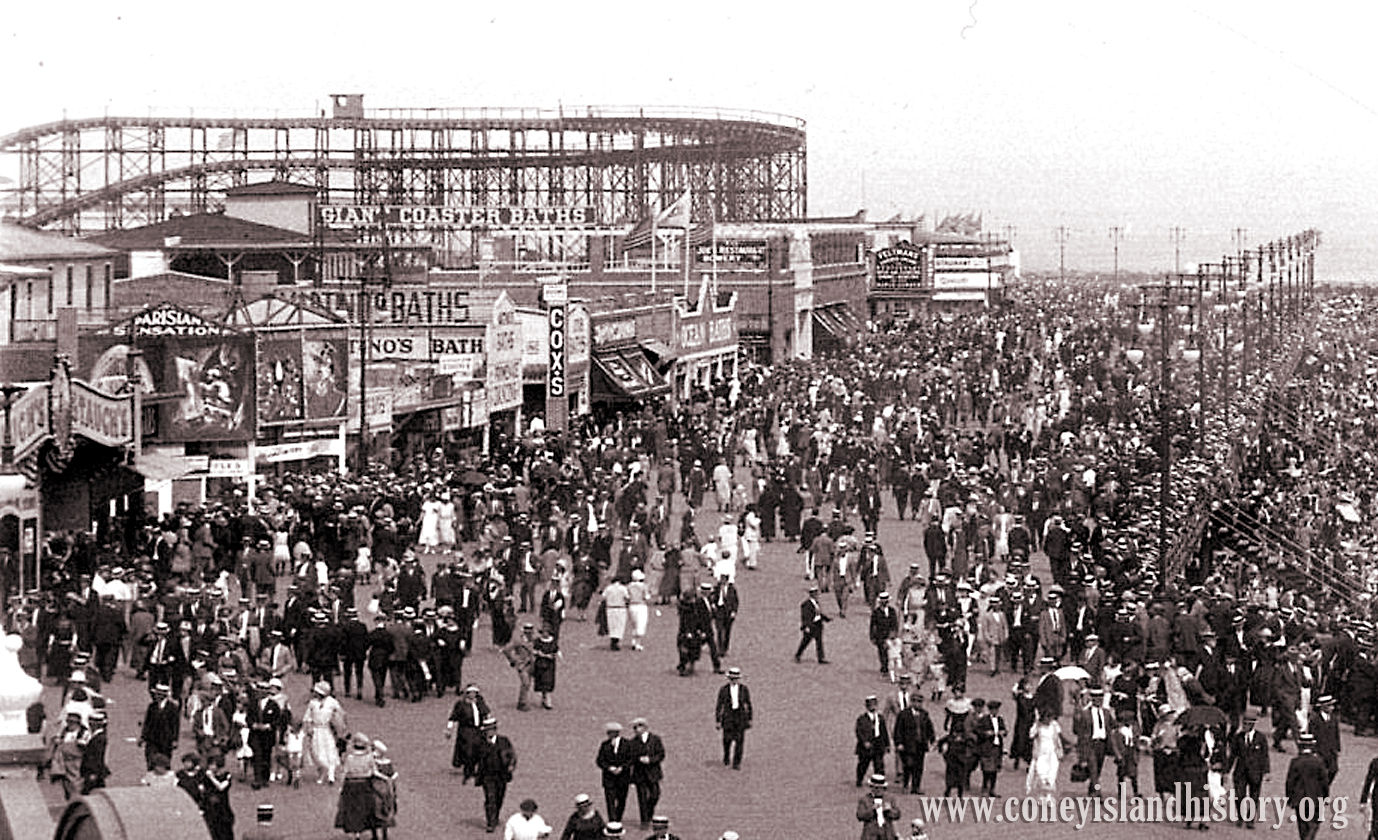

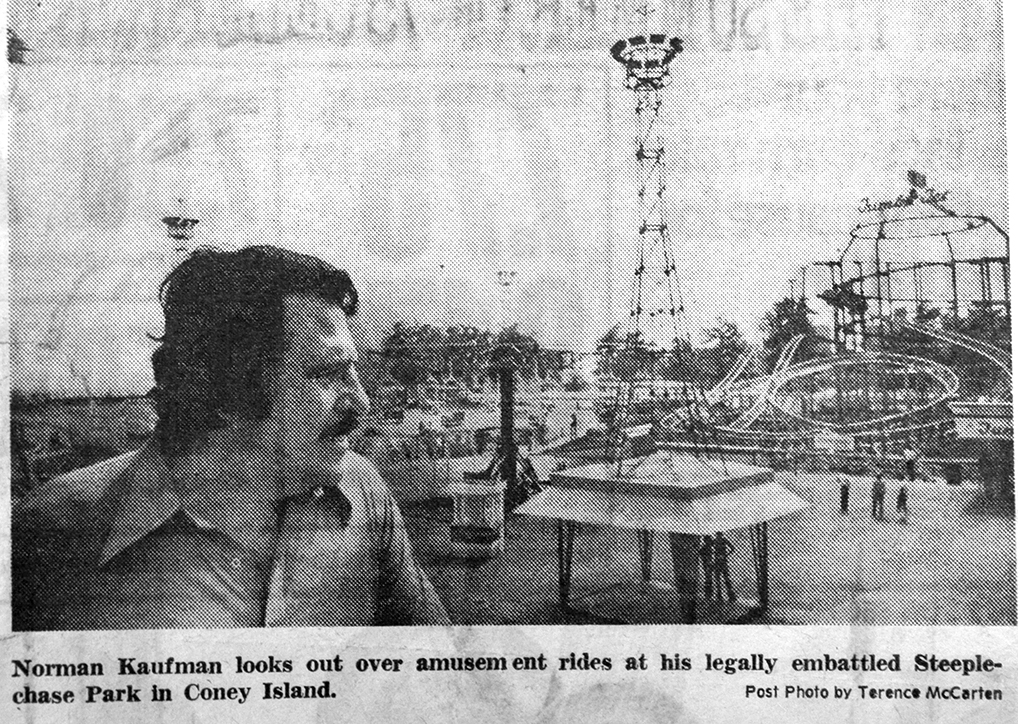

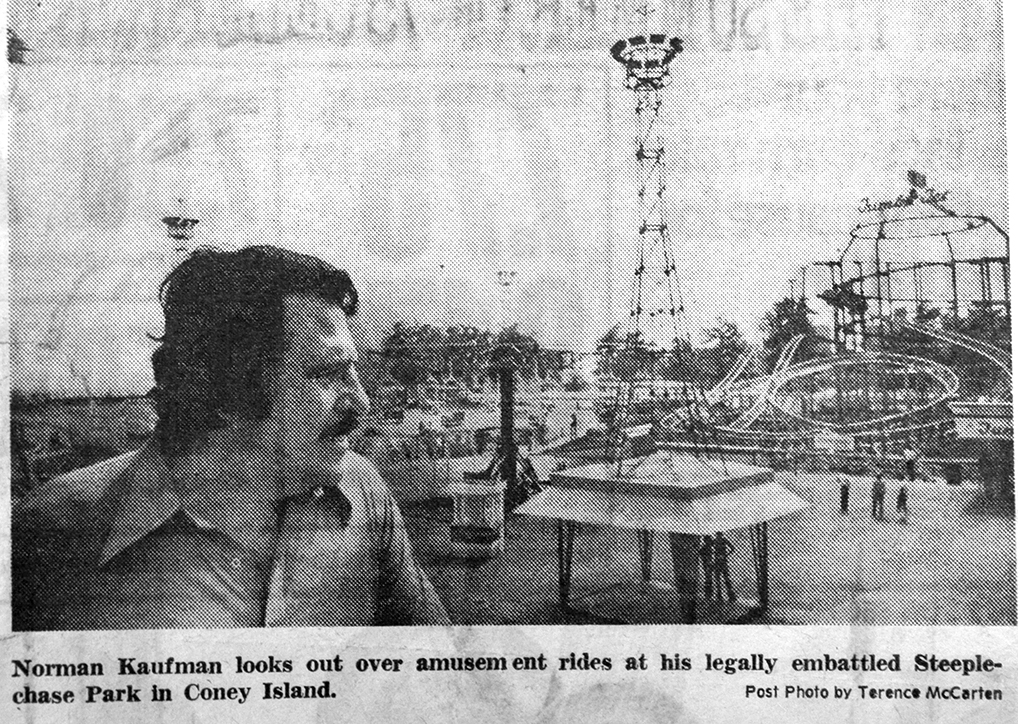

Norman Kaufman's frustrating battle with developer Fred Trump during his attempt to resurrect Steeplechase Park was a major chapter in my book, Coney Island Lost and Found and is worth repeating. In 1967, just after Trump's bulldozers finished leveling the historic park, Norman leased half of the vacant site for $20,000 a year to build a parking lot. Trump didn't realize, however, that Norman was a dreamer with ambitious plans. Norman began adding rides and concessions to his parking lot until he had pieced together an odd little amusement park that he named "Steeplechase."

"I was a little stupid or naive," he told me in 1999, "I thought that I could build up the new Steeplechase into a powerhouse that the city couldn't take away. I was thinking that I could stop whatever plans the city had for the Steeplechase site. Rather than have them come up with something, I figured I could build this amusement park into something that the city would be proud of and leave intact."

From the New York Post, June 26,1975

Norman and his partner, Irving Vichinsky, had trouble with landlord Fred Trump right from the start. The Steeplechase site was below grade and had to be leveled for parking. Trump's lease required Norman to spread ash on the parking lot surface, and Norman found a way to get the ash for free. Dewey High School was under construction on a site near the Coney Island transit yards that had once been used as a dumping ground for ash from steam locomotives. The builders needed a place to dispose of the excavated material, and Norman provided one for free: Steeplechase Park.

"Trump thought that we made a fortune by letting them dump the ash on his property," Norman told me. "He counted the trucks coming in and thought we were putting something over on him. But I never made a dime from it." Trump accused Norman of taking advantage of him, threatened to terminate the Steeplechase lease, and placed a sign over the park's entrance that read: "closed by order of the landlord."

Trump then came to the site with a pail and a shovel and began taking samples of the ash. "He put it in his car," Norman recalled, "and said to me, 'I'm gonna have this tested, Kaufman. You don't have ash here.' It was a pressure play. At times Trump would park his Cadillac in front of my entrance, so I said, 'You're blocking me off, Trump.' He'd say, 'I know what's going on here, Kaufman. You got no lease. You have to get out now. He was shoveling and yelling, 'You got no lease.' Whether you were big or small, that's the way he did business. It was always at your own level."

The harassment escalated when Norman began to install rides in the parking lot. "Trump didn't like the idea that I was bringing in rides rather than parking. He was getting a percentage and thought we'd make more money with parking than by taking up space with amusement equipment." Norman came in one morning to find his big parking sign knocked down, so he put it back up. The next day, he discovered a mound of debris blocking the entrance so he called a builder friend to clear it away. A few days later, a heavy chain appeared across the entrance, but Norman had it cut down. "Trump came back," Norman told me, "and said, 'Hey Kaufman, you got my chain. Give me back my chain.' He wanted us out."

Norman took out a restraining order against Trump and also went to the Sixtieth Precinct to file an enforcement complaint against the developer. Trump couldn't understand why Norman wasn't intimidated by him and seemed to enjoy the confrontations. "He couldn't figure out how I operated," Norman said. "He thought I was connected, but I wasn't connected to anybody. Trump wanted to put the pressure on us to get an increase in rent. He was a tough guy but we figured out a way to get to him. He had a tremendous memory and would remember everything that ever took place from the time you started with him. He'd rattle it right through and he would just keep going and never stop talking. You never had a chance to get a word in. What Irving and I did was distract him and then I could tell him my thoughts. As one of us distracted him, the other would jab away with our point. It worked."

By drawing people down the Bowery past Sixteenth Street, just as the original Steeplechase Park had done, the park kept the west end of Coney's amusement area alive. Many people dismissed Norman's park because they compared it with the original Steeplechase Park. The unfair comparisons bothered Norman: "We had fourteen kiddie rides and twenty-six majors and spectaculars. A major is a standard ride. A spectacular is something that's unusual. There were quite a number of spectaculars, like the Jumbo Jet, the Italian Skooter rides, and a German swing ride. We were the first ones to have this new equipment, and it was better than average. These were newer rides that Coney Island didn't have for many, many years."

The midway at Kaufman's Steeplechase, circa 1970. © Charles Denson

By 1968, the park was attracting large crowds. Trump was happy because he was getting a percentage, so he extended Kaufman's lease. Then, much to Norman's surprise, Trump offered him a job. "He liked that I got ahead and won," Norman said. "Trump don't like anybody winning but him. But I knew he was just being cute with his offer."

After failing to obtain a zoning change to build high-rise housing, Trump sold the Steeplechase site to the city in 1969 for $4 million, clearing a $1.5 million profit. The city was legally required to continue Norman's lease for $20,000 a year, the same deal he had with Trump

In 1972 Norman learned that the Steeplechase horse race, the namesake ride that the Tilyous had sold to Pirate's World Park in Dania, Florida, was up for sale. Norman bought the ride and sent twelve workers to Florida to number the tracks, horses, and various other pieces, and then trucked them back to Coney Island for a future reassembly on the original site. He stored the ride in shipping containers while he made plans to rebuild it. The horses made the papers in 1975 when they were stolen but later found in Pennsylvania and returned. The ride was never reassembled, but one of the original Steeplechase horses is now on display at the Coney Island History Project, courtesy of Norman Kaufman.

The pressure to evict Norman's amusement park intensified in 1974 when the city tried to raise his yearly rent from $20,000 to $158,446. It was during this dark period that Fred Trump began calling to offer his support. "He called me up and said, 'Listen, Kaufman, it's good to be in the papers. Don't worry about it. It's good that they know ya.'"

Norman finally realized that his plans were hopeless and closed his Steeplechase Park in 1981, when the city paid him $750,000 to leave the site. In 1983, Steeplechase was developed into public open space. A year later, the site became a city park, the first "special events" park in the city's history. The Brooklyn Cyclones ball park (now MCU Park) was later built on the site. In 2009, the city rezoned the entire MCU Park parking lot and most of the surrounding area for high-rise housing, fulfilling Fred Trump's dream of reducing Coney Island's amusement zone.

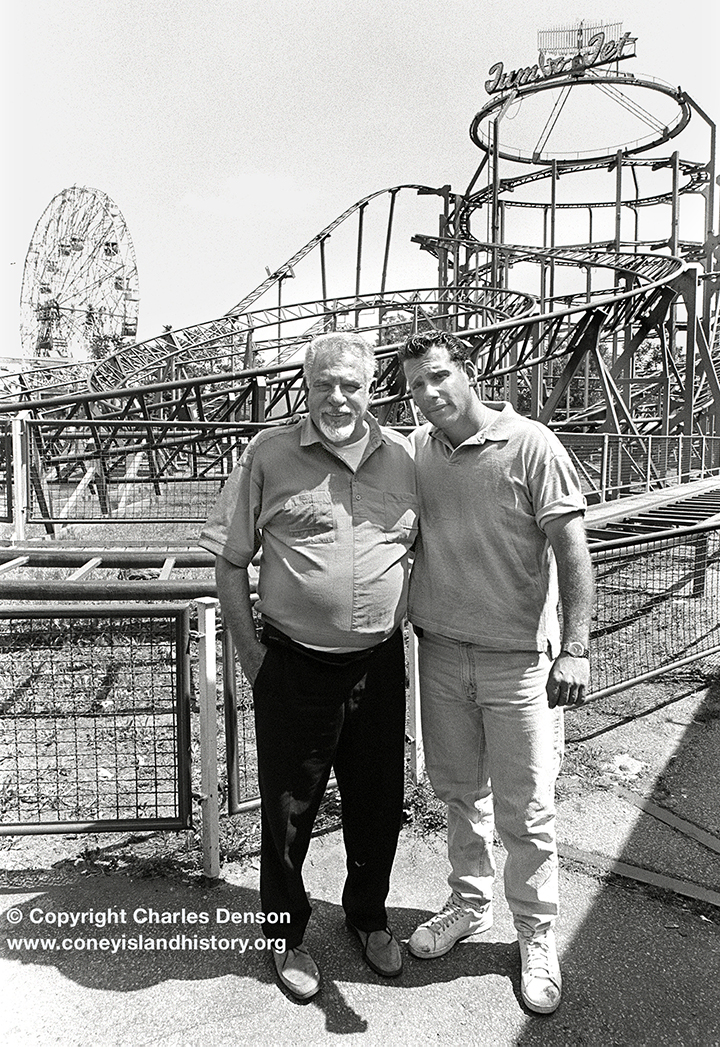

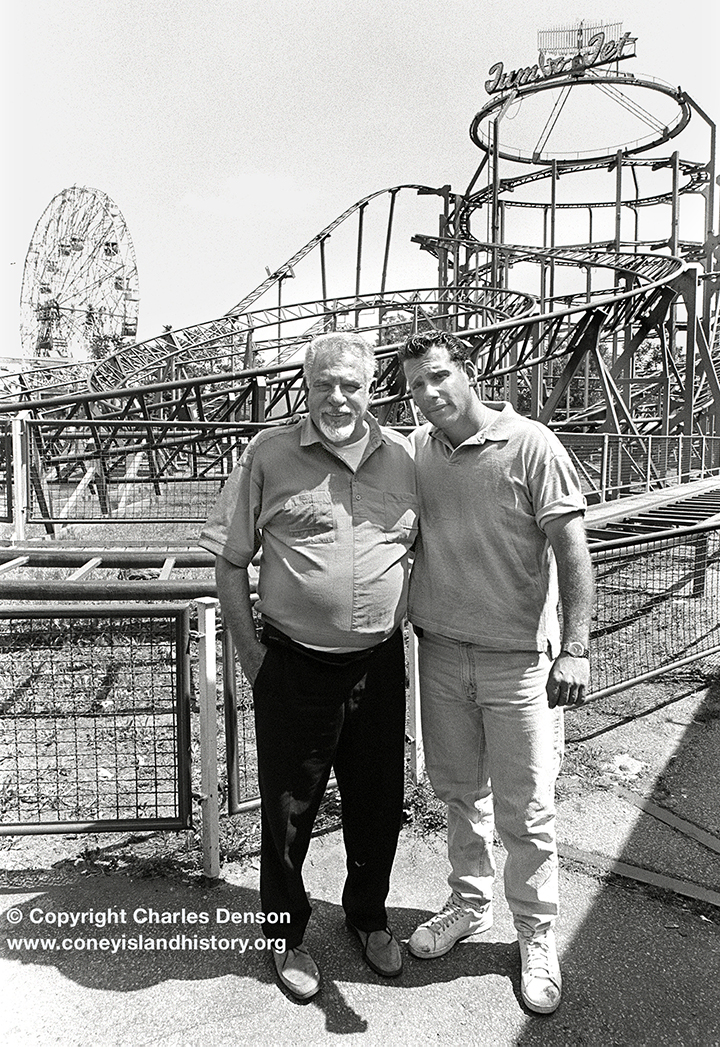

Norman's next amusement project, operated with his son, Kenny, was located on Stillwell Avenue and the Bowery after Stauch's Baths, the Bobsled, and the Tornado Roller Coaster were demolished. The Jumbo Jet Coaster, batting cages, and Go-Karts became some of Coney Island's most popular attractions in an age when the amusement area was shrinking. His last attraction was a Mini Golf Course that he constructed in 2002 a few years before the city began rezoning the area, forcing the eventual closure of all his attractions.

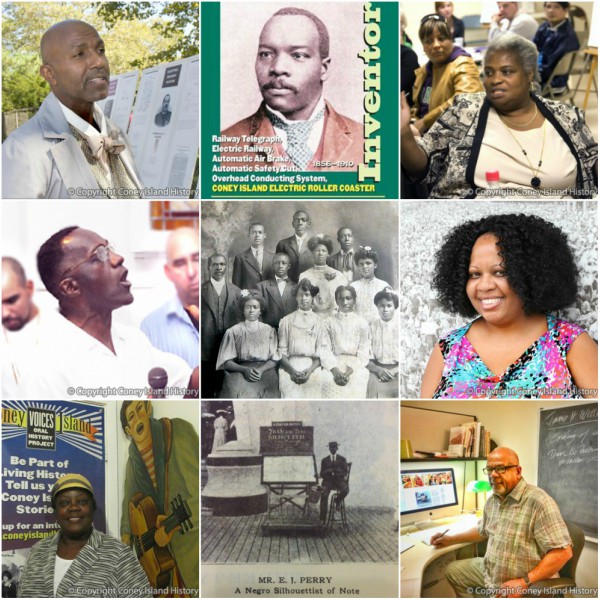

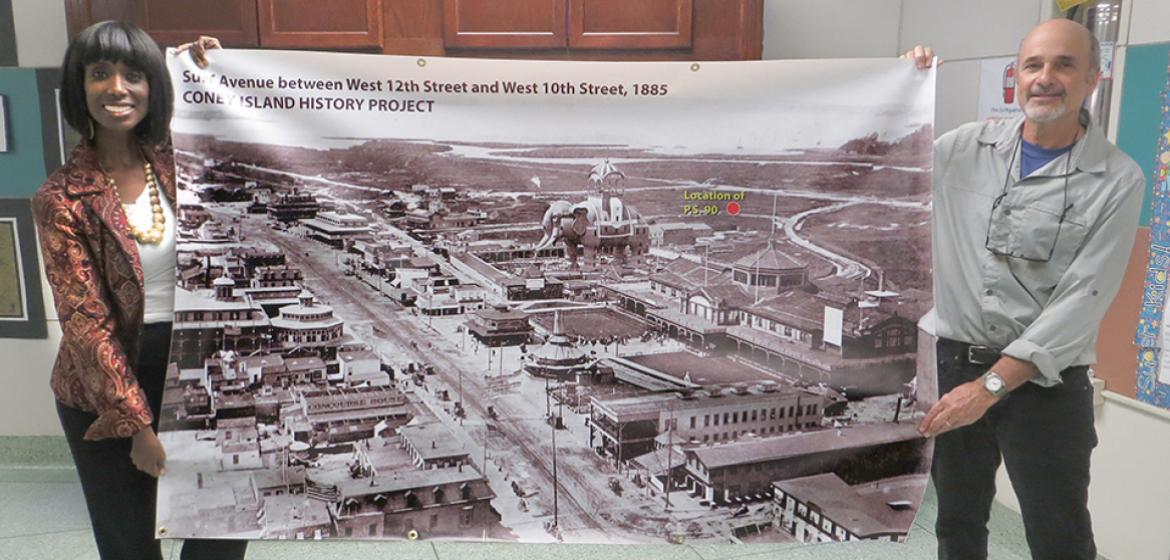

Norman Kaufman will be sorely missed. He was a big fan of the Coney Island History Project and lent us many artifacts for our exhibit center. As Coney Island loses its identity and slides into a corporate entity, it's important to remember independent impresarios like Norman Kaufman, "the Buddha of the Midway," a generous man with imagination who was not afraid to do battle with the powers that be.

– Charles Denson

Norman Kaufman and his son Kenny in front of their Jumbo Jet Roller Coaster, 1999. Photo © Charles Denson